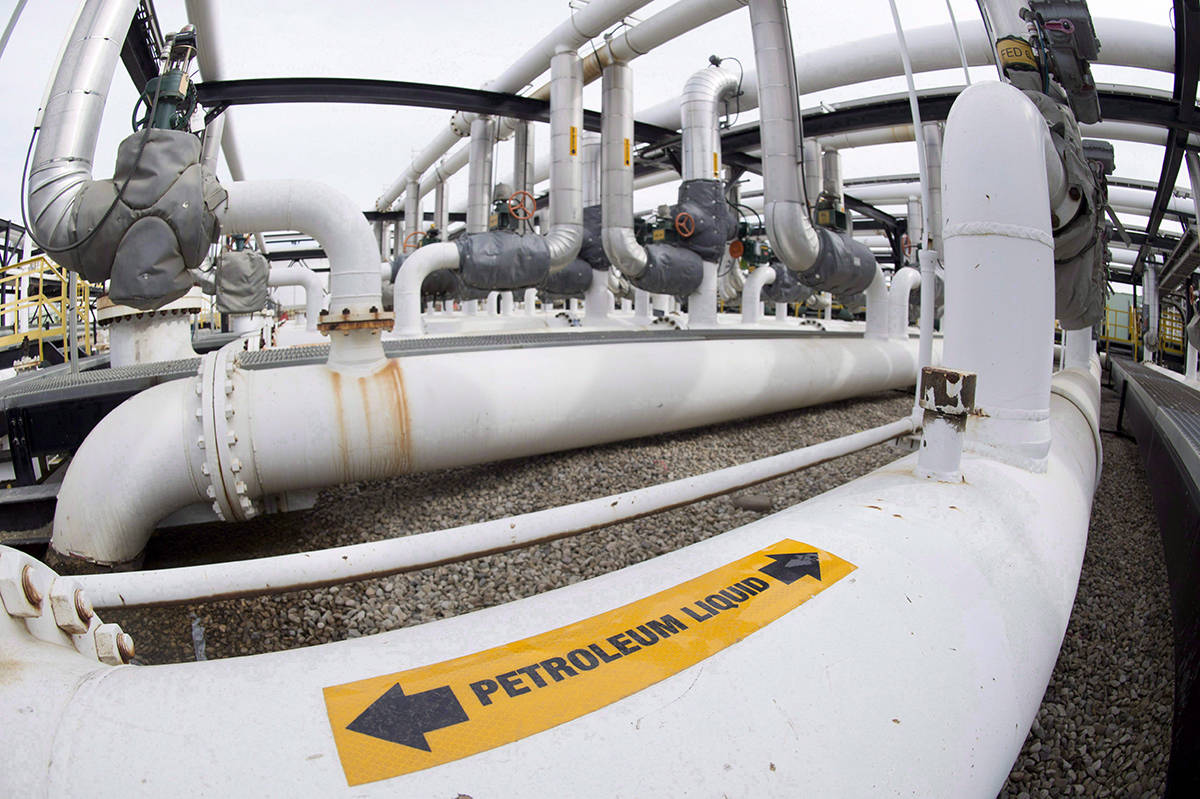

Environmental legislation proposed by British Columbia is targeting the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion and would significantly impact it, says the proponent of the project.

Maureen Killoran, a lawyer for Trans Mountain ULC, is asking the B.C. Court of Appeal to reject proposed amendments to the province’s Environmental Management Act that would create a permitting system for heavy oil transporters.

B.C. has argued the proposed rules are not intended to block the project but instead aim to protect its environment from spills and would require companies to pay for any damages, but Killoran disagreed.

“Trans Mountain will be directly and significantly impacted by the proposed legislation. Indeed, we say it is the target of the proposed legislation,” she told a panel of five judges on Thursday.

Killoran said Trans Mountain, which has operated since 1953, is the only pipeline that transports liquid petroleum to the West Coast and the only pipeline to which the legislation would apply.

The proposed law presented more risk than private-sector proponent Kinder Morgan was willing to accept, prompting it to sell the pipeline and related assets to Canada for $4.5 billion last year, she said.

Since the expansion project was first officially proposed in 2013, Killoran said it has been through the largest review in the National Energy Board’s history, a number of court challenges and faced protesters and blockades in B.C.

READ MORE: Canada says B.C. trying to impede Trans Mountain with pipeline legislation

The energy board ruled the expansion, which would triple the capacity of the pipeline, is in the Canadian public interest because the country cannot get all its available energy resources to Pacific markets including Asia, she said.

First Nations, the cities of Vancouver and Burnaby, and environmental group Ecojustice have delivered arguments in support of B.C.’s proposed rules, in part because of concerns about the local impacts of possible spills.

Killoran said the energy board recognized that there is a wealth of evidence about the fate and behaviour of diluted bitumen and there is further research underway.

The board also disputed the views of project opponents including Vancouver that the company hadn’t provided enough information about disaster-response plans, and recognized that spill prevention was a part of pipeline design, she said.

The Appeal Court is hearing a reference case filed by B.C. that asks whether the province has the authority to enact the amendments. Canada opposes the amendments because it says Ottawa — not provinces — has exclusive jurisdiction over inter-provincial infrastructure.

The Trans Mountain pipeline runs from the Edmonton area to Metro Vancouver and the expansion would increase the number of tankers in Burrard Inlet seven-fold.

B.C.’s proposed permitting system would require companies that want to increase the amount of heavy oil they’re transporting through the province to apply for a permit. Companies would have to meet conditions, including but not limited to providing disaster response plans and agreeing to pay for accident cleanup.

Joseph Arvay, a lawyer representing B.C., has argued that if a project proponent finds a condition too onerous, it can appeal to the independent Environmental Appeal Board or, in the case of Trans Mountain, to the National Energy Board.

But Killoran said Thursday that the energy board only created the special process for Trans Mountain after the company asked for it, and the province opposed it.

“While Mr. Arvay talks about it being an efficient route to solve problems, it was not ideal and it was not a route that Trans Mountain felt it should have to take. It was one that it felt it ought to take given the amount of opposition it had received.”

Laura Kane, The Canadian Press