It was a predatory attack by a starving bear that they wouldn’t have had time to react to.

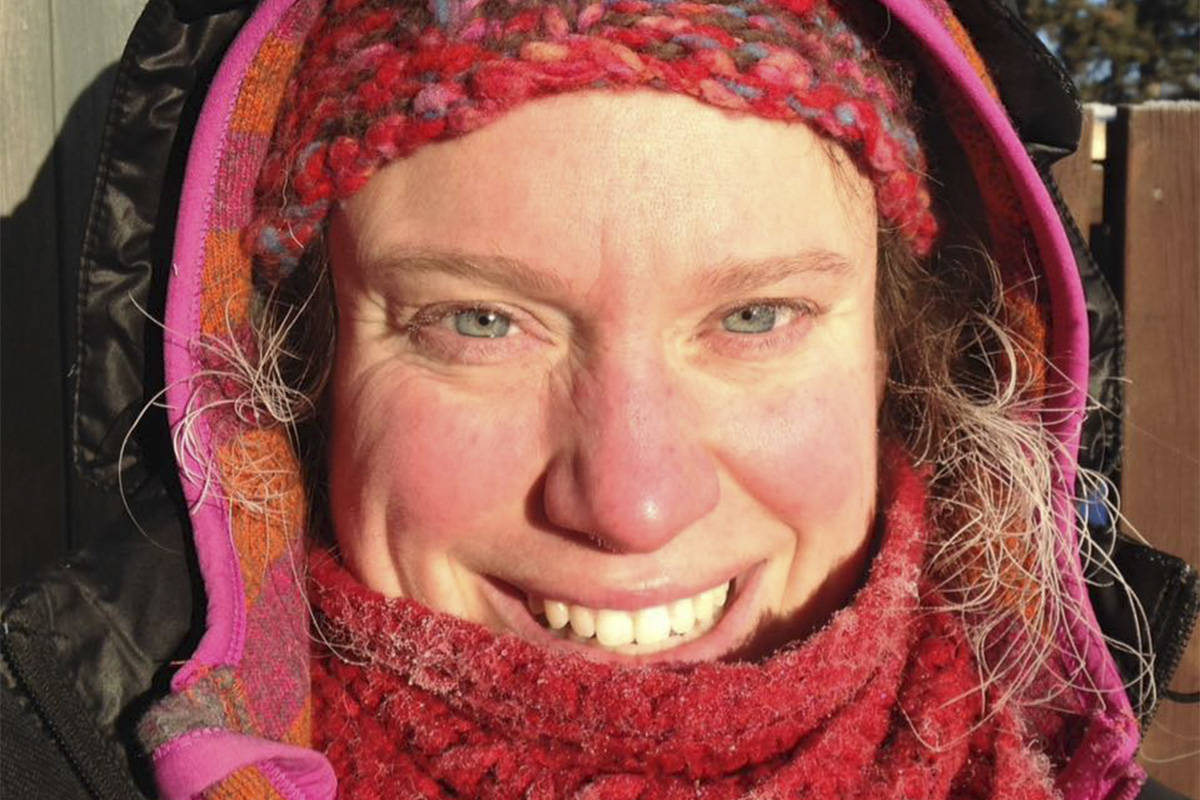

That was the conclusion of the investigation into the deaths of Whitehorse teacher Valérie Théorêt, 37, and her daughter, 10-month-old Adèle Roesholt, who were killed by a grizzly bear near their remote cabin in northeastern Yukon last year.

READ MORE: Woman, 10-month-old child dead after bear attack in Yukon

“To say the victims were at the wrong place at the wrong time sounds trite, but our investigation shows that, more than anything else, this was an unfortunate tragedy and little could have been done to prevent it,” said Environment Yukon’s director of conservation officer services, Gordon Hitchcock, at a news conference on Wednesday.

According to the coroner’s report, Théorêt, her partner, Gjermund Roesholt, and their daughter had flown to their cabin on Einarson Lake, about 200 kilometres northeast of the village of Mayo, last October.

The family, who had extensive outdoor experience, had intended to live off the land and trap until the new year, when Théorêt was to begin teaching again.

The morning of Nov. 26, 2018, Gjermund left to check on one of the family’s traplines. It snowed lightly, and as he was coming back that afternoon, he noticed fresh bear tracks that were following his snowmobile tracks from that morning, heading towards the cabin.

Gjermund arrived at the cabin and noticed no other tracks around. No one was in the cabin, so he walked towards a sauna on the property, and then onto a small trail, calling his family’s names and carrying a loaded 7 mm Remington Magnum rifle.

Suddenly, he heard a growl, and a grizzly bear charged at him from out of the bush.

He fired two shots at it, and then another two after the bear dropped to the ground, fatally injured.

The bodies of his partner and baby were nearby, and he called for help.

READ MORE: 18 bears killed in the Yukon between April and July in 2018

The subsequent investigation found that the bear was an emaciated 18-year-old male grizzly that would not have been able to hibernate because its complete lack of body fat.

In its apparent desperation to avoid starving, it had eaten a porcupine – unusual prey for bears – and was likely in chronic and severe pain because of the quills in its face, paws and digestive system.

The bear appeared to have detected Théorêt, with Adèle in a carrier on her back, on a trail and had hidden under thick tree branches.

It was from there it launched its attack, and after killing the two, dragged their bodies off the trail. Théorêt’s injuries “were consistent with the bear striking out and biting her,” while Adèle’s “were instantly incompatible with life.”

Hitchcock and Yukon Chief Coroner Heather Jones said it happened so quickly that even if she had been carrying bear spray or a gun, Théorêt would not have had time to react or fight back.

“What makes this incident especially tragic is that the family took proper precautions to prevent something like this from happening,” Hitchcock said. The cabin and surrounding space were kept clean and free of attractants.

The report makes three recommendations, focusing on continued efforts to inform the public that bear encounters can happen in the Yukon anywhere and during any season.

There have only been two other fatal bear attacks in the Yukon over the last 22 years — one in Ross River in 2006, and in Kluane National Park in 1996.