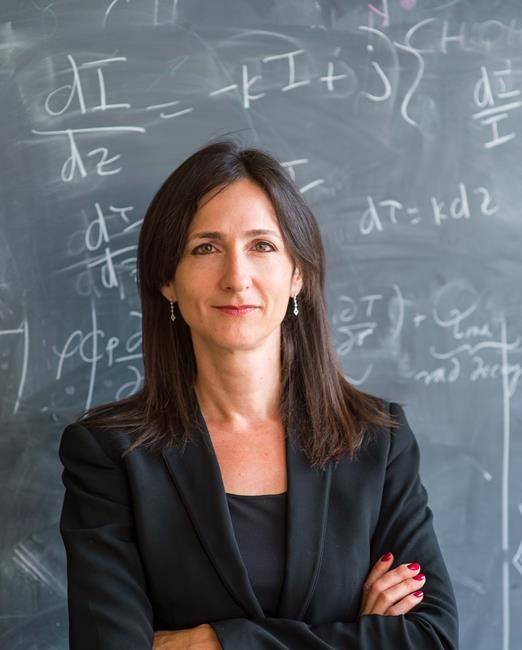

Sara Seager has pledged to spend the rest of her life searching for another Earth among the billions of stars that inhabit our night sky.

“That’s our goal: to find life out there,” the Toronto-born astrophysicist says in a distinctly assured monotone, as if describing a walk to the local mall.

The highly acclaimed professor, who is scheduled to deliver a lecture on the heady topic later this week in Halifax, says the lofty objective is well within reach for the first time in human history.

And she should know.

“Forty years ago, people got laughed at when they searched for exoplanets,” she says, referring to planets found beyond our solar system. “It was considered incredibly fringe because it’s so hard … But there’s this shifting line of what is crazy.”

Seager, who teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is considered one of the world’s leading experts on exoplanets. She has been profiled by The New York Times, CNN and Cosmopolitan, and won a MacArthur “genius” grant.

In the field of astronomy, she is a certified rock star.

Ultimately, her research could help answer some of the biggest questions facing humankind. But first, Seager and her team have plenty of work to do.

And that’s what she plans to talk about Friday when she delivers the third annual MacLennan Memorial Lecture at Saint Mary’s University.

Her mission to find alien life somewhere in the cosmos may sound like it was borrowed from an episode of “The-X Files,” but recent advances in astrophysics suggest this pioneer of planet hunting has good reason to be optimistic.

Prior to the 1990s, only two planets — Uranus and Neptune — had been discovered in the 4,000 years since the Babylonians looked up and recorded the celestial comings and goings of visible stars and planets. Pluto wasn’t spotted until 1930, but it was demoted to dwarf planet status in 2006.

There was a huge breakthrough in 1995, when two Swiss astronomers announced they had found the first planet outside our solar system orbiting a sun-like star. They called it 51 Pegasi B. Its existence was inferred by measurements showing its gravity is causing the star to wobble.

And then in 2014, NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope was used to find Kepler-186f, the first Earth-sized exoplanet in a star’s so-called Goldilocks zone.

“It’s where a planet is not too hot, and not too cold, but just right for life,” says Seager.

Thanks to rapidly improving computers and detection equipment, scientists have found more than 3,600 exoplanets in the past 30 years.

However, only 52 of them are in that habitable zone, where water in its liquid form may exist.

But being in the zone doesn’t automatically mean an Earth-sized exoplanet could support life as we know it.

“Until we can study the planet’s atmosphere … we really won’t know anything about that planet,” says Seager. “It doesn’t really mean anything until we get a better look.”

That’s not as easy at it sounds. Many of the recently discovered exoplanets are too far from Earth for direct observation.

But a tantalizing solution may have presented itself in August 2016, when researchers at the European Southern Observatory in Chile detected an Earth-sized exoplanet orbiting the habitable zone of the red dwarf Proxima Centauri, our solar system’s nearest neighbouring star at only 4.2 light years away.

That’s about 40 trillion kilometres away, but it’s still about 10 times closer than Kepler-186f.

“It was right next door, although very hard to find,” says Seager. “In astronomy, close really matters.”

Still, directly observing a relatively small planet that closely orbits a much larger star is tough because the intense light generated by the star must be blocked.

“Planets don’t have energy,” says Seager, “All they’re doing is reflecting light from the star. They’re like the little kid on the block … It’s hard for them to shine.”

That’s why the planetary scientist is working with NASA and Northrop Grumman to develop Starshade, which will be shaped like a daisy and stand taller than a 15-storey building. Deployed by spacecraft, the petal-shaped panels — first proposed in the early 1960s — would block waves of starlight that would otherwise overwhelm an accompanying space telescope.

“That’s my favourite project,” says Seager. “One of my life’s goals would be to make Starshade happen.”

She wants to adapt a new space telescope — the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope or WFirst — to make it “Starshade ready” by the time it is ready for launch in the 2020s.

With Starshade, Seager hopes to study the atmospheres of exoplanets to determine if they have oxygen and other gasses that may indicate they are supporting alien life.

“When I help find all these planets, the goal is to … look for signs of life by way of gasses (like oxygen) that don’t belong,” she says. “We won’t even be 100 per cent sure that it’s made by life … And if it is, we won’t know if it’s intelligent beings or just slime.”

Seager recalls her introduction to astronomy, while growing up in Toronto, was attending her first outdoor “star party,” where amateur astronomers gather under dark skies to share their knowledge — and their telescopes.

Though her father David — a well-known expert in hair-transplant procedures — would try to dissuade her from becoming an astronomer, Seager would later earn a bachelor of science in math and physics at the University of Toronto, before earning a PhD in astronomy at Harvard.

She says the math suggests there is life out there. But finding it won’t be easy, given the vastness of space.

“I know that it could be a multigenerational search,” Seager says. “It could be a really, really long time.”

Michael MacDonald, The Canadian Press