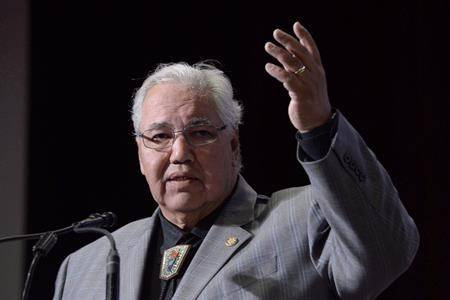

Sen. Murray Sinclair says if the child-welfare system existed in its current form when he was a boy, he would have been cut off from his family and cultural heritage.

The chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on residential schools and Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge was raised by his grandparents just outside Winnipeg.

“We would have been apprehended by the child-welfare system if it had been organized as it is today,” he told social workers, bureaucrats and academics at a national child welfare conference Friday.

He said his grandparents would have been deemed too old to have cared for him, had today’s rules applied. Their house didn’t have electricity or running water and was crowded.

“We sometimes didn’t have enough to eat. We barely had enough wood in the winter time to keep the place warm, but we managed,” he said.

“And we managed because of the strong-willed nature of my grandmother who insisted that everybody participate in the raising of those children, those little children who came into her life.”

Sinclair said there are more children in Canada’s child-welfare system today than there were at the height of residential schools, which housed Indigenous children forcibly taken from their communities in what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission said amounted to cultural genocide.

“The monster that was created in the residential schools moved into a new house,” Sinclair said. “And that monster now lives in the child- welfare system.”

Sinclair’s home province of Manitoba has the highest per-capita rate of children in care in the country. As of March 31, there were more than 10,300 kids in care — almost 90 per cent Indigenous.

Sinclair said some children may flourish in non-Indigenous foster families, but the vast majority have been failed because they have been cut off from their family traditions.

“They come out of it not knowing where they come from, where they’re going, why they’re here and who they are.”

Sinclair said most social workers want to do good, but must acknowledge they are working in a system that hurts Indigenous children.

“They have to … be willing to stick their necks out a bit and do what is the right thing within the rules they’re bound by, instead of defaulting to a view that is founded on principles of racism that go back 150 years,” he said in an interview.

Not enough has been done to recruit Indigenous people into decision-making roles and nearly two-thirds of the urban population have been ill-served by reserve-run child-welfare agencies, he added.

Monty Montgomery, a University of Regina social work professor with 25 years experience in Indigenous child welfare, said training and resources for First-Nations-run welfare organizations are slowly improving.

“What we’re really talking about is incremental change and we don’t notice it maybe from week to week or month to month,” said Montgomery. “There is progress and good things are happening here.”

Alex Scheiber, who chairs a committee of provincial and territorial child-welfare leaders, said tinkering with the system isn’t good enough. Simply adding more Indigenous social workers and policy-makers won’t suffice.

“There’s a reason why it’s hard to retain and attract Indigenous people. We’re asking them to come and work in a system that is failing their people,” he said.

Scheiber said he’s encouraged by steps taken by his home province of British Columbia to shift more decision-making to First Nations.

And he believes there’s reason for optimism.

“I have had the feeling over the last 18 months that we are on the brink of the biggest change in child welfare in Canadian history,” he said.

“I would like to think that within 10 years time, we will look back at this period of time as being transformational.”

Lauren Krugel, The Canadian Press