South Korea on Tuesday offered high-level talks with rival North Korea to find ways to co-operate on next month’s Winter Olympics in the South. Seoul’s quick proposal following a rare rapprochement overture from the North a day earlier offers the possibility of better ties after a year that saw a nuclear standoff increase fear of war on the Korean Peninsula.

In a closely watched New Year’s address, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un said Monday that he was willing to send a delegation to the Olympics, though he also repeated fiery nuclear threats against the United States. Analysts say Kim may be trying to drive a wedge between Seoul and its ally Washington in a bid to reduce international isolation and sanctions against North Korea.

Kim’s overture was welcome news for a South Korean government led by liberal President Moon Jae-in, who favours dialogue to ease the North’s nuclear threats and wants to use the Pyeongchang Olympics as a chance to improve inter-Korean ties.

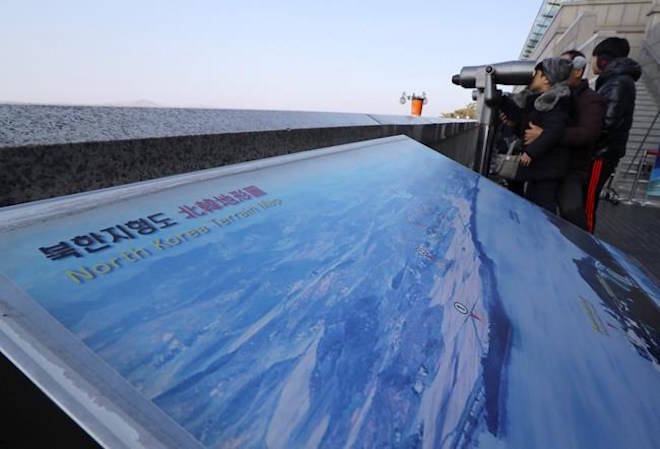

Moon’s unification minister, Cho Myoung-gyon, proposed in a nationally televised news conference that the two Koreas meet Jan. 9 at the shared border village of Panmunjom to discuss Olympic co-operation and how to improve overall ties.

Earlier Tuesday, Moon spoke of what he described as Kim’s positive response to his earlier dialogue overtures and ordered officials to study how to restore talks with North Korea and get the North to participate in the Olympics.

North Korea did not immediately react. But if there are talks, they would be the first formal dialogue between the Koreas since December 2015. Relations between the Koreas have plunged as North Korea has expanded its weapons programs amid a hard-line stance by Moon’s conservative predecessors.

Last year, North Korea conducted its sixth and most powerful nuclear test and test-launched three intercontinental ballistic missiles as part of its push to possess a nuclear missile capable of reaching anywhere in the United States. The North was subsequently hit with toughened U.N. sanctions, and Kim and President Donald Trump exchanged warlike rhetoric and crude personal insults against each other.

Kim said in his speech Monday that North Korea last year achieved the historic feat of “completing” its nuclear forces. Outside experts say that it’s only a matter of time before the North acquires the ability to hurl nuclear weapons at the mainland U.S., but that the country still has a few technologies to master, such as a warhead’s ability to survive atmospheric re-entry.

Talks could provide a temporary thaw in strained inter-Korean ties, but conservative critics worry that they may only earn the North time to perfect its nuclear weapons. After the Olympics, inter-Korean ties could become frosty again because the North has made it clear it has no intention of accepting international calls for nuclear disarmament and instead wants to bolster its weapons arsenal in the face of what it considers increasing U.S. threats.

“Kim Jong Un’s strategy remains the same. He’s developing nukes while trying to weaken international pressure and the South Korea-U.S. military alliance and get international sanctions lifted,” said Shin Beomchul of the Seoul-based Korea National Diplomatic Academy.

He said the North might also be using its potential participation in the Pyeongchang Olympics as a chance to show its nuclear program is not intended to pose a threat to regional peace.

In his address Monday, Kim said the United States should be aware that his country’s nuclear forces are now a reality, not a threat. He said he has a “nuclear button” on his office desk, warning that “the whole territory of the U.S. is within the range of our nuclear strike.”

He called for improved ties and a relaxation of military tensions with South Korea, saying the Winter Olympics could showcase the status of the Korean nation. But Kim also repeated that South Korea must stop annual military exercises with the United States, which he calls an invasion rehearsal against the North.

About 28,500 American troops are stationed in South Korea to help deter potential aggression from the North, a legacy of the 1950-53 Korean War, which ended with an armistice, not a peace treaty.

Hyung-Jin Kim, The Associated Press

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.