Some long-ago murder stories – regardless of the ‘closure’ of convictions – never diminish in psychological staying power.

The horrific Cook case which rocked Stettler and Central Alberta in June of 1959 is one such example. Raymond and Daisy Cook and their five children were found shot and bludgeoned to death in the garage of their Stettler home.

Eldest son Robert Raymond Cook, 21 at the time, was convicted of the crimes in the Old Red Deer Court House. He was retried later in Edmonton and again found guilty. He was executed in November of 1960 by hanging.

Penned by Calgary Playwright Aaron Coates, The End of the Rope recently had a very successful run at Bashaw’s Majestic Theatre. Organizers staged the play to raise funds for the town’s centennial celebrations in 2011 and a two-volume area history which will be available later this fall. The End of the Rope chronicles the experiences of Cook and his lawyer Dave MacNaughton during their 18-month battle to evade the noose. Cook had a history of clashes with the law during his short life — prior to the murders, he had been in prison on a robbery charge.

Bashaw is connected to the case because Cook was apprehended on a farm near the town by police after a sprawling, ambitious manhunt. He was then whisked away to the village’s police office.

Leanne Walton, secretary of the Bashaw Historical, said the play resonates with locals.

“I think people are still wondering if he was truly guilty or not,” she explains, adding that the case was largely built on circumstantial evidence. Walton grew up along nearly Hwy. 53 near Bashaw and recalls the frantic search for Cook.

“That was probably one of the times many of us out in the country locked our doors at night.”

Glen Weins, 77, describes how Cook was found on his cousin’s farm near town.

“They found Cook’s 1957 Monarch abandoned about two miles from our place. The RCMP came to our home and told us he was on the loose, and that we had to watch for him,” says Weins, who is on the board of the Bashaw Historical Society and the Museum.

Cook was finally caught on Norman and Verna Dufva’s farm. Norma, who is Weins’ cousin, saw Cook emerge from one of their barns. She contacted police, grabbed her two young children and fled from the house.

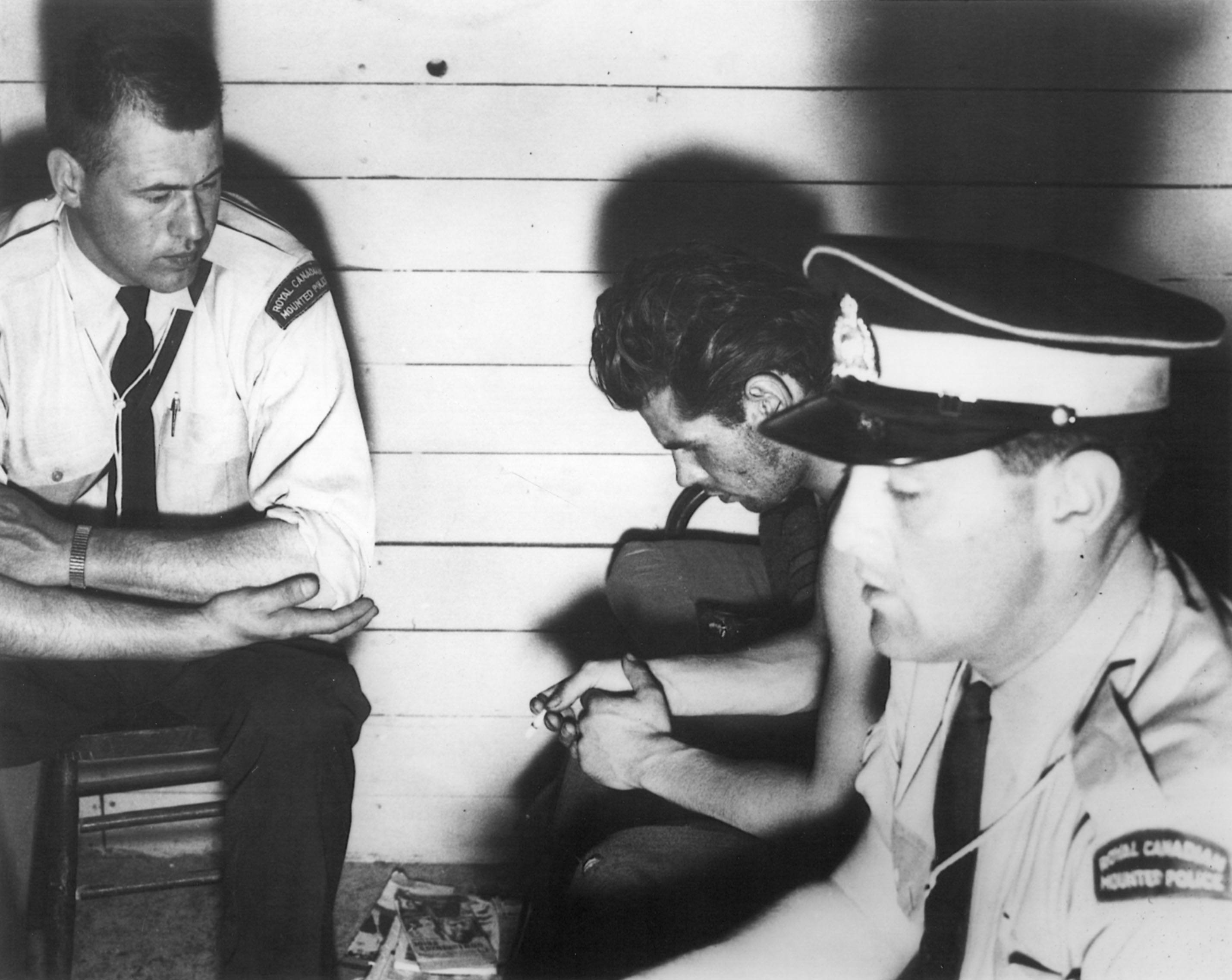

Police finally captured Cook and took him to the Bashaw detachment which is now the Bashaw Museum. About 400 people gathered to watch the bedraggled escapee escorted into the building.

Today, visitors can see the small cell Cook was held in. Photos and newspaper articles about the case cover the walls which have changed little since Cook was held there.

Emil Stauss recalls standing across the street watching Cook taken into custody.

“I really didn’t think he could accomplish all of that by himself. I can’t see one person killing that many. They slept in different rooms. How could he get them all? You would think one of the children might get away, one of the older ones.”

As pointed out earlier, questions linger as to Cook’s guilt. His alibi of being in Edmonton during the night of the murders couldn’t be cracked, although pinpointing the times of the deaths wasn’t the exact science that it is today. And although he reportedly didn’t always see eye to eye with his folks, some say it’s an enormous stretch to believe he would butcher his entire family. Also, police seemed to abandon the search for other suspects.

In a letter to his lawyer, Cook wrote he “Used to think it was up to the Crown to prove a person guilty, now, I believe different. I know they cannot prove me guilty, for in all truth, I am not. If I hang, murder will be committed in the name of the law.”

For more about the Bashaw centennial or the history books, call Leanne Walton at 403-784-3437.