By Michael Dawe

Red Deer Express

Today, June 21st, is National Aboriginal Day. It is an annual event, designated by the Federal Government, to, “Celebrate the unique heritage, diverse cultures and outstanding achievements of Canada’s three aboriginal peoples – the First Nations, the Inuit and the Metis.”

Most attention recently has been focused on the great troubles and tribulations of aboriginal peoples.

Certainly, that is a very important part of history and modern day life that should never be overlooked and/or forgotten.

One example locally would be the Red Deer Indian Industrial School which operated just west of the City of Red Deer from 1893 to 1919.

Many of the horror stories one hears about residential schools were part of the history of that Red Deer school. At the turn of the last century, Dr. P.H. Bryce, chief medical officer for Canada’s Departments of the Interior and Indian Affairs wrote that of all the Indian Industrial Schools that he examined, the one at Red Deer had the worst mortality rate.

What should not, however, be overlooked/forgotten are the great triumphs of the First Nations way of life.

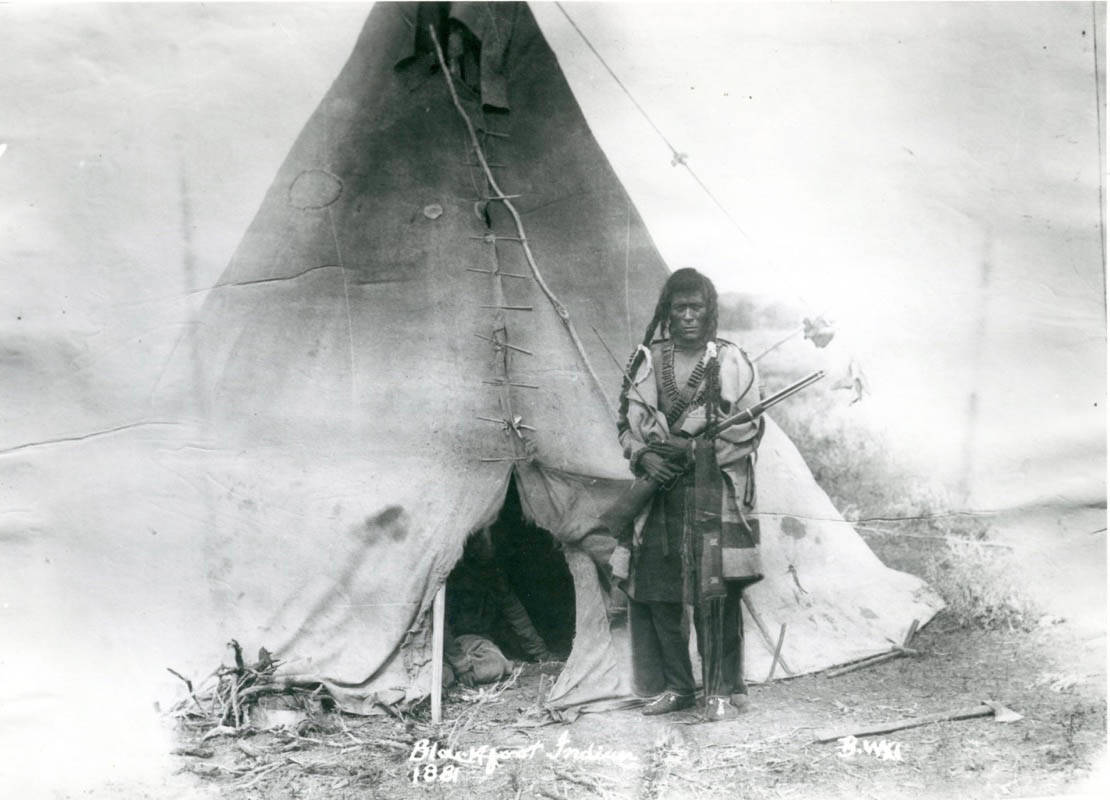

Central Alberta was the part of North America where the horse and gun were first combined. What followed was an era of great wealth and power for the First Nations of this region.

For millennia, the bison, often referred to as buffalo, covered the parklands and prairies in numbers which are hard to imagine today.

The First Nations became highly efficient harvesters of this resource, including through the use of pounds and buffalo jumps, both of which were found in Central Alberta.

However, given the mobility and speed of the bison herds, the acquisition of the horse made hunting even more productive and efficient.

The First Nations would no longer have to wait for the bison to come. With horses, they could more quickly locate the herds and chase them.

Traditional hunting weapons, such as arrows and spears, had become quite effective over the millennia. Guns and bullets were even more efficient, particularly when the animals were at some distance.

Once guns and horses were combined, food, clothing, and shelter, as well as many domestic implements made from the animals, became very plentiful. The local First Nations thrived.

The journals of the early explorer, Anthony Henday, who visited the area in the mid-1700s, give an indication of the extent of the wealth and power that was experienced at the time.

He described a large Blackfoot (Soyi-Tapix) encampment on the west side of Pine Lake.

The camp consisted of at least 200 large teepees. They were arranged in two long rows with a broad ‘avenue’, nearly a kilometre in length, down the middle. At the one end, was the chief’s tent. It was large enough to comfortably accommodate 50 people. In the centre was a large white buffalo robe, upon which were seated 20 elders smoking grand pipes.

There was food in tremendous abundance.

Boiled buffalo meat was served in large baskets. Large haunches roasted on the fire. Henday was given a special gift of 10 large buffalo tongues as a welcoming present.

This wonderful and comfortable life continued for a few generations. However, it tragically came to an end as the nineteenth century progressed.

The vast bison herds began to vanish, not by the harvesting of the First Nations, but rather because of extreme over-hunting by others.

There were epidemics of diseases that the First Nations had never experienced before – smallpox, measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever and others. In some of these epidemics, as many as half of the First Nations living in what is now Alberta perished.

The last wild bison to be seen near Red Deer were spotted 10 km north of the Red Deer River Crossing in the summer of 1884. There were a mere six animals in the herd.

The era of starvation and destitution was tragically now well established.