While Jaclyn Andrews can’t rationally explain her fear of clowns, she’s been avoiding them for years.

Walking the midway at local fairs is totally out of the question, and lately she’s considered double checking with fellow parents before attending kids’ birthday parties.

She realizes that might sound a little silly to some, but the clowns that haunted her nightmares as a young girl still evoke bad feelings.

“I’m panicked, can’t breathe, sweaty,” says Andrews, 35, describing how she feels when she sees a clown.

“I get the overwhelming need to get out — and now.”

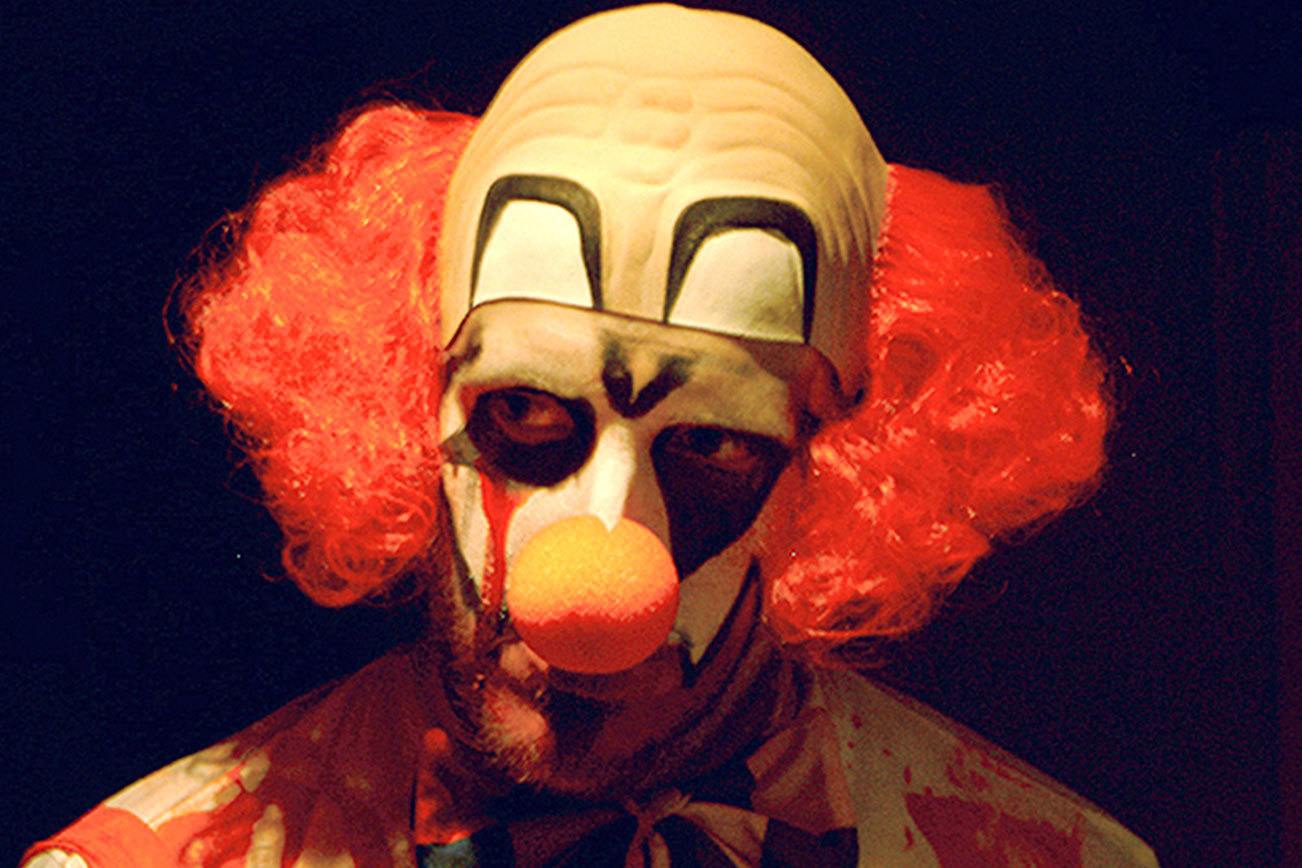

The fear of clowns, known as coulrophobia, is a relatively new phenomenon with very little research behind it. And while it’s not considered an official phobia by the World Health Organization, its sufferers say the experience is very real.

Pshh, you guys are afraid of EVERYTHING. #ITMovie pic.twitter.com/iMxYsc0SoM

— IT Movie🎈 (@ITMovieOfficial) August 28, 2017

Andrews, a resident of Hamilton, feels anxious thinking about the days ahead when evil clowns will be a focal point of popular culture and practically impossible to avoid.

A remake of Stephen King’s “It” arrives in theatres next week and is expected to draw huge audiences intrigued by the titular shapeshifter, also known as Pennywise, who often takes the form of a clown.

And the upcoming sixth season of “American Horror Story,” which begins airing Tuesday on FX Canada, is generating buzz for the return of Twisty, a demented clown with a taste for trickery and murder.

Clowns have existed since ancient Egypt, although their trademark white faces and colourful costumes weren’t established until the early 1800s when British entertainer Joseph Grimaldi began playing Joey the Clown. A similar look was adopted by Scottish businessman John Bill Ricketts when he brought the modern circus to the United States a few years later.

For many decades the happy-go-lucky personas of modern clowns like Bozo and Ronald McDonald seemed in style, but a notorious American serial killer is considered to be the inspiration for the advent of the more sinister brand of clowns.

Before he was convicted for the murders of 33 young men in 1980, John Wayne Gacy seemed like a relatively average guy, who sometimes dressed as Pogo the Clown, a character he created while volunteering at children’s hospitals. After he was jailed, Gacy painted portraits of himself in clown costume and the artwork became the focus of exhibitions — and protests.

“People learn to be afraid from the movies they see, and from the news they read — watching other people be afraid,” said Martin Antony, a professor of psychology at Ryerson University.

“Gacy may have triggered certain directors and writers to portray clowns in that way, and that may have exacerbated fear of clowns.”

Two years after Gacy’s conviction, the film “Poltergeist” featured a scene in which a young boy is dragged under his bed by a toy clown brought to life in the middle of the night. And King’s novel “It” was released in 1986 and adapted for TV in 1990, with Tim Curry playing the creepy Pennywise.

Andrews swears watching the “It” miniseries in middle school scarred her for life, especially moments like its opening scene in which a young boy is lured by the killer clown to a sewer.

”(‘It’) just did it in for me,” she says.

The fascination with vicious clowns only grew as “It” became a favourite at video stores during the 1990s and other forgotten films like 1988’s “Killer Klowns from Outer Space” found another life on DVD alongside the clown-like doll used by serial killer Jigsaw in the “Saw” horror movies.

Much to the dismay of professional clown performers, those portrayals helped take the wholesomeness out of a character once considered a fixture of family entertainment.

Rami Nader, a psychologist at the North Shore Stress and Anxiety Clinic in Vancouver, says some people are leery of clowns because they fear their exaggerated painted smiles obscure their true emotions, which makes them unpredictable.

“You don’t know really what they’re feeling, what they’re thinking or what they’re going to do,” Nader says.

A spate of creepy-clown sightings reported across North America last year didn’t help their negative perception. Perhaps inspired by popular prank videos on YouTube, reports of individuals wandering through neighbourhoods while wearing menacing clown masks began to spread. In the U.S., Target stopped selling scary clown masks as a result.

Frank McAndrew, a professor of psychology at Knox College in Illinois, says he learned how deeply opinions of clowns have eroded after his study of “creepiest occupations.”

The online survey, which canvassed 1,341 people, found respondents were bothered by people whose jobs held ambiguous threats, and in particular individuals who made physical contact or exhibited “non-normative, non-verbal behaviour.”

Clowns ranked as the creepiest, worse than taxidermists, sex shop owners and funeral directors.

McAndrew says he found the ambiguity of a clown’s performance art seemed to rattle the respondents the most.

“(They said), ‘We don’t know if there’s something to be afraid of, but we have a paralysis about not knowing whether we should be scared,’” he said.

The professor also discovered some members of the clown community weren’t exactly helping rebuild their reputation as non-threatening. After his study was published, McAndrew said some clowns began to “stalk” him on social media and called the president of his college in an attempt to get him fired.

But McAndrew also found that discussions about his findings online revealed a stark apathy from even those who aren’t afraid of clowns.

“I don’t recall seeing anybody ever saying, ‘You know, I really like clowns,’” he added.

David Friend, The Canadian Press